Biomes - Russie

|

Biomes - Russie |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| transport | Fuseaux horaires | climat | Biomes | histoire | admin | politique | économie | infrastructure | médias | éducation | org |

Biomes en Russie |

|

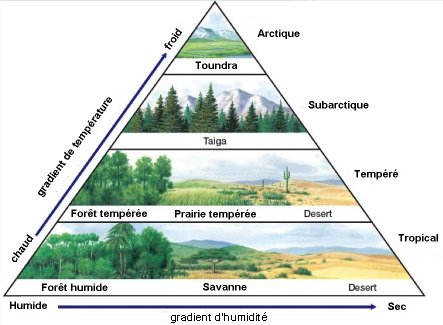

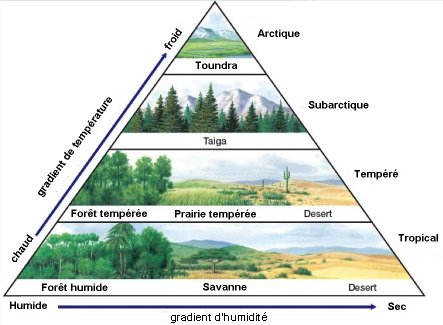

| Les biomes du nord de l'Eurasie sont similaires à ceux de l'Europe ou de l'Amérique du Nord : toundra au nord; taïga et forêts de feuillus au milieu; steppe et désert au sud. L'extrême sud a des déserts ou une végétation arbustive subtropicale de type méditerranéen. Les limites des biomes correspondent étroitement aux principaux types de climat. |

|

| Pendant des millions d'années, le nord de l'Eurasie et l'Amérique du Nord ont été connectés l'un à l'autre - principalement à travers le détroit de Béring, mais aussi parfois via le Groenland et la Scandinavie. Cela a abouti à un éventail d'animaux et de plantes qui sont partagés par ces deux régions. En fait, une grande partie du biote est si similaire que les biogéographes regroupent les deux dans un seul domaine biogéographique «holarctique». La flore et la faune de l'Inde (qui est sur le même continent que la Russie), d'autre part, sont complètement différentes de celles du nord de l'Eurasie; ils ressemblent plus à ceux de l'Afrique. Par exemple, l'Amérique du Nord et la FSU partagent de nombreux genres d'arbres (p. Ex. Pin, épicéa, orme, érable, bouleau, tremble et chêne). La plupart des espèces d'arbres sont différentes, mais plusieurs se ressemblent - les espèces dites «vicariantes». Par exemple, le pin cèdre de Sibérie (Pinus sibirica) ressemble généralement au pin blanc d'Amérique du Nord (P. strobus); le pin de Norvège (P. sylvestris) est très similaire au pin rouge du Minnesota (P. recinosa). Aux niveaux inférieurs du règne végétal (par exemple, parmi les mousses), la similitude est encore plus grande. De vastes étendues de forêts boréales de la Russie et du Canada renferment les mêmes mousses (Dicranum, Polytrichum, Pleurozium) et Cladonia lichens, par exemple. Il y a un degré plus élevé de différence entre les plantes à fleurs et les herbes, mais de nombreuses fleurs sauvages russes sont toujours immédiatement reconnaissables aux botanistes américains en visite comme une «renoncule», une «violette», un «muguet» ou une «pantoufle de dame», ”Même s'ils ne savent pas avec certitude quelles espèces ils recherchent. La similitude générale est la plus grande entre l'est de la Russie et l' Alaska , les anciennes parties du pont terrestre de Béring Источник: https://geographyofrussia.com/biomes/ |

|

|

|

| De nombreux genres ou même espèces d'animaux sont identiques en Amérique du Nord et dans le nord de l'Eurasie: Arctiqueet les ours bruns, les loups gris, les renards roux, les orignaux, les élans, les aigles royaux, les faucons pèlerins et les mésanges à tête noire, par exemple. S'il manque une correspondance exacte, il existe généralement une assez bonne espèce de substitution / vicariante (par exemple, le vison d'Amérique et le vison eurasien, les loutres, les castors, les grues, les corbeaux, etc.). Les différences entre les oiseaux chanteurs sont les plus importantes, car la plupart des oiseaux migrateurs en Amérique du Nord proviennent des néotropiques, tandis que ceux du nord de l'Eurasie sont originaires d'Afrique ou d'Asie du Sud. Par exemple, les fauvettes ou les moucherons eurasiens ne sont pas apparentés aux oiseaux américains du même nom, bien qu'ils soient similaires dans leur écologie et leur comportement. Certains biomes apparemment similaires présentent également un degré plus élevé de différence et d'endémicité. Par exemple, l'Extrême-Orient russe partage des combinaisons remarquables de plantes et d'animaux avec des zones situées soit au sud (Chine), soit au nord (Tchoukotka). Aucune forêt de ce type n'existe en Amérique du Nord. Une grande singularité est observée dans les écosystèmes des zones côtièresLa Californie et le sud de la Floride à la place, et il n'y a pas d'analogues forts pour de tels écosystèmes en Eurasie. Les cinq principaux biomes de la FSU (toundra, taïga, forêt de feuillus, steppe et désert) s'étendent à travers le continent eurasien en larges ceintures d'ouest en est. Entre les deux, il existe des types de transition (p. Ex. Forêt-toundra, forêt mixte et forêt-steppe). Chaque biome ou zone naturelle a un climat correspondant, un type de sol zonal et un ensemble caractéristique de plantes et d'animaux. Certains biomes sont plus étendus que d'autres, selon le modèle climatique. En outre, certains sont considérablement mieux conservés que d'autres. Par exemple, alors que la majeure partie de la zone de la taïga reste raisonnablement intacte, avec des forêts à couvert fermé (même dans les zones à forte exploitation forestière), 99% de la steppe vierge a disparu. La diversité globale des plantes et des animaux en Russie n'est pas grande, en raison de sa situation au nord. Par exemple, il existe 11 000 espèces de plantes vasculaires, 30 d'amphibiens, 75 de reptiles, 730 d'oiseaux et 320 de mammifères en Fédération de Russie. En comparaison, les États-Unis (un pays plus méridional de la moitié de la taille de la Russie) comptent 19 000 espèces de plantes vasculaires, 260 amphibiens, 360 reptiles, 650 oiseaux et 360 mammifères. |

|

|

|

Источник: https://geographyofrussia.com/other-biomes/ |

|

| Tundra | |

Treeless tundra is found in the north of Russia, generally above the Arctic Circle. In European Russia, it occupies limited space on Kola Peninsula and in the Arkhangelsk and Komi regions along the coast. In Siberia, the most extensive tundra is found on Yamal, Taymyr, and Chukotka Peninsulas. In North America, tundra covers much of Alaska's North Slope, as well as about one-quarter of Canada. The word “tundra” comes from the Saami people and means “treeless.” North of the tundra, the polar desert has virtually no life. Some hardy blue-green algae, and occasional mosses and lichens, are about all that can be found there. Nevertheless, even the northernmost islands of Russia, in Franz Joseph Land, have a flora of 57 flowering plants, 115 lichens, and 102 mosses. Polar bears, seals, and walruses are important mammals of the surrounding seas and ice. A few species of hardy Arctic birds—murres, puffins, gulls, and terns—live on inaccessible cliffs in “bird bazaars.”

|

|

| In contrast to the polar desert, the tundra has hundreds of species of plants and scores of birds and mammals. Although the precipitation in the tundra is low (usually under 300 mm per year), the evaporation rate is even lower, thus creating familiar soggy summer conditions. Soils are of the “tundra glei” type (“gelisols,” in the U.S. classification), with a pronounced anaerobic zone. Underneath is permafrost, but the top 20–30 cm of soil near the surface can team with life in the summer months. These soils are subject to much frost churning, which pulls organic matter down the profile and brings rock fragments to the surface, creating spectacular patterned grounds. The most common plants of the tundra are mosses and sedges. Dwarf shrubs, grasses, and forbs become more common in the southern tundra. Eventually, bigger shrubs and even small trees begin to appear as one travels farther south, giving way to forest–tundra. In European Russia this zone is located around the Arctic Circle (66?32'N); in Siberia it begins farther north, at about 70?N. In European Russia the treeline is formed by Scotch pine, spruce, or birch; in Siberia it is mainly larch. Climatically, the treeline corresponds to the point at which the mean July temperature goes above 10?C. Typical animals of the tundra include Arctic foxes, reindeer, lemmings, gyrfalcons, swans, geese, ducks, various shorebirds, snowy owls, horned larks, redpolls, and buntings. Some are rare or endangered (e.g., Siberian red-breasted geese, Siberian cranes, and rosy gulls). There are many protected areas in the tundra biome: however, most of them are poorly accessible. The biggest three are the Great Arctic Zapovednik on the Taymyr Peninsula, the delta of the Lena River, and Wrangel Island. | |

| Taïga | |

“Taiga” is a Siberian word; it has recently become better known through the efforts of the Taiga Rescue Network, doing important conservation work throughout the Northern Hemisphere. In North America, taiga is known as the “boreal coniferous forest,” which is what covers much of Canada. Note that although the West Coast forests of British Columbia, Oregon, and Washington also have conifers, they have a much higher diversity of plants and much bigger trees, so they are not the true taiga. In Northern Eurasia, the taiga is a huge biome (covering over half of all Russia), but it is rather monotonous. In European Russia the main species are Scotch pine, Norway spruce, and European fir; in western Siberia they are Scotch pine, Siberian cedar pine, and Siberian fir and spruce; and in eastern Siberia they are two species of larch. Coniferous but also deciduous, larch is the only tree that can survive the brutal cold of the Verkhoyansk area, which is the coldest in the Northern Hemisphere. Birch and aspen may be found as secondary-growth species on clearcuts and fire clearings. Low shrubs with berries of the Vaccinium group are very common, as are mosses and lichens. Interspersed with big trees are nutritionally poor bogs with peat mosses (Sphagnum), Labrador tea, cranberries, and carnivorous sundew (Drosera). The boreal forests of Eurasia make up about 21% of the world's total tree cover on 5.3 million km2; this area is twice the size of Argentina! |

|

| From north to south, three subzones can be distinguished in the taiga: northern, middle, and southern. The biodiversity and the productivity are highest in the southern taiga, which extends south to an imaginary line from Moscow to Yekaterinburg to Krasnoyarsk. Over 2,500 species of flowering plants occur in the taiga. Some, especially orchids, can be beautiful, but are very rare. Mosses, lichens, ferns, and mushrooms thrive under the canopy of the coniferous trees. Soils of the taiga are poor in nutrients and acidic; the most typical are called “podzols,” or “spodosols” in the U.S. classification. Consequently, few crops can be grown in the taiga zone. The main crops are the hardiest grains, like barley and rye, which are raised on small clearings of land near the rivers. Meadows in the floodplains can produce good hay, and berries and mushrooms from the forest complement the diet. Typical taiga mammals include the symbol of Russia, the brown bear (the same as the North American grizzly, albeit a different subspecies). They also include gray wolves, lynxes, red foxes, Siberian sables, minks, wolverines, moose, elk, shrews, red squirrels, flying squirrels, chipmunks, and mice. The local mammal fauna ranges from 30 to 50 species. Over 160 species of taiga birds include black storks, various raptors, eagle owls, capercaillie (turkey-sized black forest chickens), grouse, black woodpeckers, waxwings, and many finches (crossbills, hawfinches, siskins, etc.). Some of the same species occur in North America. The best places to visit taiga in European Russia include the Darwinsky, Tsentralno-Lesnoy, Kivach, and Kostomuksha Zapovedniks and the Paanayarvi, Vodlozerski, Kenozerski, and Valdaiski National Parks. For the ultimate in European taiga, the virgin forests of the Komi Yugyd Va area near the polar Urals are worth a visit; this is the largest remaining fragment of original forests that covered northern Russia and Scandinavia, and it is a World Heritage Site. In Siberia, most of the taiga can be observed directly along the Trans-Siberian Railroad, although much of it is secondary growth. More pristine landscapes include Visimsky Zapovednik in the central Urals and Yuganski Zapovednik in the Tyumen region. Lake Baikal is surrounded by three zapovedniks and two national parks, and is mainly in the taiga zone. East of Lake Baikal, Zeisky and Bureinsky are two relatively new zapovedniks protecting the true wilderness of the eastern taiga. If you are only visiting Moscow and St. Petersburg, several of the forests near these cities are southern taiga as well; there are many local nature parks and wildlife sanctuaries, including Losiny Ostrov National Park, partially within the Moscow city limits! The park's name literally means “Moose Island,” and it used to be the hunting preserve of the tsars | |

| Forêts mixtes et feuillus | |

South of the taiga zone, a narrow wedge of mixed and deciduous forests stretches from the Baltic republics to the Urals and beyond, to Novosibirsk and the Mongolian border. This zone is smaller than the taiga, but it has a warmer and generally wetter climate. Moscow is located in the middle of it, with pine and spruce being more common to the north of Moscow, and oak, maple, and linden being more common to the south. The exact mixtures vary, depending on previous logging, fire history, plantings, and bedrock. The majority of secondary forests in this zone are pure birch stands, very popular among the Russian landscape artists. Deciduous forests can grow faster and utilize resources better than conifers, provided that the weather is not too cold. When autumn comes, they shed their leaves and become dormant for winter to avoid death by desiccation. Broad leaves are efficient water evaporation machines; if they are left on the trees in winter, all the water will escape the trunk. In North America the same zone is found throughout much of the mid-Atlantic region, parts of New England, Ohio, Ontario, and central parts of Wisconsin and Minnesota. Much of Western Europe likewise is in this zone. |

|

| The soils of the deciduous forest zone are gray forest soils (“alfisols”). These are richer and less acidic than the spodosols of the taiga, but are only modestly better for agricultural purposes. The main feature of these soils is a very quick turnover of nutrients. Wheat and rye are commonly grown in this zone. Forests have a well-developed layered-canopy structure, with tall trees like oaks, lindens (basswoods), or maples dominating the top laye. The second layer of smaller trees and tall shrubs (chokecherries, mountain ash, hazelnuts) give way to small shrubs and herbaceous layers, and finally a layer of moss on the ground. Mushrooms are plentiful, as well as wild berries. The deciduous forest zone is warm enough for some amphibian and reptile species as well; toads, frogs, vipers, and lizards are common. The typical mammals of the zone include many of the taiga species mentioned above. In addition, hedgehogs, martens, European roe deer, beavers, and dormice are common. Endangered European wood bison can be seen in a few preserves, such as the Prioksko-Terrasny Zapovednik, about 2 hours south of Moscow. The secretive Russian desman is an endemic of the Soviet Union; it looks like an oversized water shrew and spends most of its life in clean, slow-flowing forest rivers. It is a threatened species. The birds are very diverse, with a few hundred species present in the forests surrounding Moscow, for example. Not all of them are true forest species, but every May the forests ring with dozens of different voices. Typical forest birds include falcons, eagles, owls, woodpeckers, nuthatches, titmice, and thrushes. The famous nightingales sing majestically in early May through late June in much of European Russia. These secretive, drab olive birds with rusty tails do not look at all remarkable and are hard to see; their song, however, has 12 different parts and is remarkably rich and beautiful. They are even more common in the forest–steppe, where the legendary Kursk nightingales were greatly admired by 19th-century Russian writers and poets. The best places to see the deciduous zone in European Russia include the Prioksko-Terrasny Zapovednik, mentioned above; the Oksky Zapovednik in the Ryazan region, about 4 hours east of Moscow; and the Kaluzhskie Zaseki in the Kaluga region, about 4 hours southwest of Moscow. In Belarus on the border with Poland, the famous Belovezhskaya Puscha is home to one of the last herds of European bison. A few national parks in this zone also exist in the Baltic republics. | |

| Forêts - Steppes | |

| South of Moscow, the forest gradually gives way to the steppe. Across the Oka River, the first patches of steppe begin to appear. The Tula and Orel regions have forest–steppe, while the Kursk and Belgorod regions are primarily in the true steppe zone. The steppe stretches across much of Ukraine to the lower Volga, to northern and central Kazakhstan, and to the foothills of the Altay. Steppe forms in areas with moisture deficit that precludes tree growth. Although steppes are on average warmer than most of the forested biomes to the north, it is really the lack of water that determines the tree boundary. In North America, crossing from eastern to western North Dakota or from Iowa into Nebraska takes you across this climate boundary. In Europe, the most extensive steppes exist in Hungary. Although Eurasian steppes are warmer than the taiga zone, they can be brutally cold in winter with temperatures dropping to –40?C (plus massive wind chill). Snowfall is highly variable, and some winters see very little snow. The mean annual temperature may range from +9?C in Moldova to –6?C in the Tyva Republic. |

|

| The classic Eurasian steppe is treeless. The main plants are perennial grasses and forbs with deep root systems. They can resist droughts, fire, and cold extremely well. The two most widespread grasses are sheep fescue (Festuca ovina) and species of feathergrass (Stipa). Unlike in North America, there is no tallgrass prairie in Eurasia; its closest analogue is the northernmost and the wettest type of steppe, the meadow–steppe. One square meter of meadow–steppe can support over 50 species of flowering plants! Some shrubs (e.g., wild plum) and diverse wildflowers are common, especially members of the rose, legume, and sunflower families. The soils underneath the Eurasian steppe are the legendary “chernozems” (literally “black earths”). They were extensively studied by Vasily Dokuchaev and are similar to the “mollisols” of the United States. The topsoil may exceed 1 m in depth, and is a rich black color due to a high proportion of organic matter (10–15%). Calcium carbonate accretions occur deeper in the profile. Salinization is a common problem in the drier areas, where so-called chestnut soils become dominant. The productivity of virgin chernozem is several times greater than that of the gray forest soils or podzols, allowing a bountiful harvest with minimal fertilization. Over many years of farming, however, even the best chernozems will be depleted. There is a considerable need for irrigation, especially when spring wheat or other summer crops are grown. Soil erosion due to plowing is common. Even 5% of tree cover in the form of windbreaks may dramatically reduce erosion, and many such windbreaks were planted in southern Russia, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan in the 1950s. The typical mammals of the Eurasian steppe include steppe foxes, ferrets, wild steppe cats, saiga antelopes, field hares, ground squirrels, gerbils, jerboas, and marmots. The typical birds include demoiselle cranes, bustards, eagles, harriers, kestrels, stilts, avocets, quails, hoopoes, bee-eaters, rollers, larks, and magpies. There are also a few dozen species of reptiles, including snakes and lizards. There are few places where virgin steppe can still be seen. As in North America, over 99% of this biome in Eurasia was plowed under in the 19th and 20th centuries. There are very few restored steppe patches. However, small preserves provide glimpses of the steppe's original vegetation. The best examples in Russia include the Galichya Gora (Lipetsk), Kursky (Kursk), and Voronezhsky and Khopersky (Voronezh) Zapovedniks, as well as the Orlovskoe Poleye (Orel), Ugra (Kaluga), and Samarskaya Luka (Samara) National Parks. In Ukraine, the most famous preserve is Askaniya Nova in the Kherson region near the Black Sea. This unique territory was established by a visionary German landowner, F. Falts-Fein, in 1886. Today it is one of a handful of virgin steppe fragments left in Eastern Europe. The early history of the preserve included acclimatization experiments with exotic fauna; ostriches, zebras, antelopes, and llamas roamed the first Ukrainian safari park. Today, the descendants of many of these animals can still be seen in large enclosures. The remainder of the Askaniya Nova steppe is home to the native fauna. |

|

| Déserts | |

| With its spacious, rainless interior, Eurasia is home to the northernmost deserts in the world. Located entirely outside the tropics, the deserts of Central Asia have all the usual desert features, including sand dunes, desert pavement, rock formations, small saline lakes and playas, and very little vegetation. However, the northern, boreal elements of their flora and fauna are unique. The main deserts in North America are found at latitudes between 25? and 35?N, whereas in Eurasia they occur between 38? and 44?N. The four main deserts of Central Asia are the Kara Kum in Turkmenistan, south of the Aral Sea; the Kyzyl Kum in Uzbekistan, southeast of the Aral Sea; the Moyynqum in Kazakhstan, east of the Aral Sea; and the Saryesik Atyrau, south of Lake Balkhash. There is also a small desert north of Makhachkala and west of the Caspian Sea in Russia, in Kalmykia (the only true desert in Europe). Altogether, the Central Asian deserts occupy 3.5 million km2—an area as large as Saudi Arabia and Iran combined. |

|

| Deserts generally form in areas with potential evaporation exceeding precipitation by a factor of 10 or more. In temperate deserts, the average rainfall is <250 mm per year. The sandy desert is the most common type, with large dune fields of various shapes. The most famous dune form is the crescent-shaped “barkhan,” with horns pointing downwind. Barkhans form in areas with little vegetation. Parabolic dunes, star dunes, and longitudinal dunes are also common. Some dunes may be 30–40 m high. Most of the Kara-Kum is sandy desert (“black sand”). East of the Caspian Sea is the gravelly Ustyurt desert. There are also stony and salty deserts in Central Asia. When soils are present, they are of the desert type (“aridisols”). In the United States, such soils are common in parts of the western Great Plains and much of the Southwest. Plants of the deserts are “xerophytic,” which means they are adapted to very dry conditions. Typically they lack leaves and have extensive but shallow root systems, capable of catching whatever moisture may be available on short notice. There are no cacti, because those are native only to the Americas. Instead, Artemisia forbs and small shrubs (Atriplex, Salsola, Tamarix, and Anabasis) are widespread. One genus, saxaul (Haloxylon), grows into a small-sized tree. Unique communities develop on saline flats that are flooded during the rain period, the so-called takyrs (similar to the playas of North America). Many desert plants are adapted to tolerate severe salinity. Along the seasonal watercourses, gallery forests or tugai develop, with poplar and willow species. Reeds develop around isolated saline desert lakes. The fauna of the deserts can be surprisingly diverse, but elusive. Animals spend most of the day underground, avoiding heat; at night they are everywhere. Unfortunately, some of the most spectacular representatives of large desert mammals are now extinct (wild tarpan horses and tigers), while others are endangered (Asiatic wild donkeys, Przhevalsky horses, saiga antelopes, Persian gazelles) and are confined to a few prserves or zoos. The most common mammals are rodents (22 species); also common are insectivores, including long-eared hedgehogs, and carnivores, including weasels and wildcats. Birds are represented by eagles, Asian pheasants, sand grouse, pratincoles, desert jays, crested larks, and desert wheatears. Reptiles thrive in this biome, with monitor lizards, agamas, skinks, epha vipers, cobras, and others. There are some spectacular butterflies, beetles, cicada, and spiders in the deserts as well. Gerald and Lee Durrell (1986) provide some excellent descriptions of the ones they found in the Repetek preserve of Turkmenistan. |

|

| Autres biomes | |

Besides the main five biomes of Northern Eurasia, there are some rarer types, of which four merit mention here:

All mountain ranges have their own zonation of ecosystems from bottom to top. For example, in the Karachaevo-Cherkessia Republic of Russia in the northern Caucasus, the following ecosystems are found: true steppes (200–500 m above sea level); oak–hornbeam forests (500–1,300 m); beech forests (1,300–1,500 m); fir–spruce forests (1,500–1,700 m); pine forests (1,700–2,100 m); subalpine tall-grass vegetation (2,000–2,500 m); and alpine short-grass vegetation (2,500–3,200 m). Snow and glaciers extend above the highest alpine vegetation. The lower timberline is determined by moisture availability, and the upper by temperature during the vegetative season. The timberline at about 2,100–2,500 m is formed by a krummholz of crooked pines, beeches, birches, aspens, and other trees that grow only as tall as shrubs. In the subalpine belt, rhododendrons, tall forbs from the rose and sunflower families, and some tall grasses play an important role. In the alpine zone, graminoids (grasses, sedges, rushes) and forbs (roses, pinks, primroses, and sunflowers) predominate. The exact sequence and elevation of the vegetation belts are determined by the direction of the slope (north-facing slopes are always colder and have a lower treeline) and by local climatic and biological factors. The treeline, for example, occurs at 300 m in the polar Urals and the Khibins in the Kola Peninsula in the Arctic, but at 2,000 m in the Carpathian mountains, 2,500 m in the Caucasus, and above 3,000 m in much of Central Asia (which is considerably warmer and drier). The main species at the treeline will also differ among mountain ranges. In much of Siberia it is Siberian cedar pine shrub (Pinus pumila), while in the Caucasus it may be birch, beech, or Scotch pine. Subtropical vegetation can be found at the southern tip of the Crimea Peninsula; in a narrow strip along the Black Sea coast of Russia and Georgia; and in the southeastern corner of Azerbaijan (Lenkoran) along the Caspian Sea coast. These areas all have a subtropical C-type climate, where frosts do not occur even in January. Protected by the mountains from the cold northern wind, these sheltered areas can support Mediterranean-like vegetation. Of the three areas, the Crimean Peninsula is the driest; its native communities consist predominantly of sclerophyllous scrub, but cork oaks, junipers, wild madro?os, pistachio trees, and other unusual plants are well represented. Visually, it bears a striking resemblance to the vegetation of Italy and Greece, much farther south. Much of this native ecosystem has been replaced with fruit orchards, vineyards, and parks full of introduced Mediterranean trees and shrubs (e.g., cypresses, cedars of Lebanon, Italian pines, and palms). Massandra and Livadia Parks, and Nikita Botanical Garden at Gurzuf, have particularly famous arboreta. The Black Sea coast has lush vegetation forming under wetter conditions. Native plants include many evergreen shrubs or small trees (boxwood, laurel, yew, etc.). Many of these are relics of the much warmer Tertiary period, 2–65 million years ago. Lianas and epiphytes are common in the forests. Tea and tangerines can be planted and survive winters here. In Russia, the Great Caucasus Zapovednik near Sochi, including a famous box–yew grove, can be visited for the best representative look at the whole Black Sea coast ecosystem. In Georgia, a few preserves and arboreta existed in the Soviet period (e.g., the Pitsundo-Mussersky Zapovednik south of Gagry and the Sukhumi Botanical Garden); however, many of these are now in the separatist province of Abkhazia, and their status and ease of access are thus uncertain. The Lenkoran region of southeastern Azerbaijan is covered with humid subtropical forests with many Tertiary relics well represented (ironwood, chestnut oak, Hyrcanian box tree, Lenkoran acacia, and others). The Hirkan National Park protects over 150 rare and endemic plant species along with many native bird and mammal species with limited distribution. The unique mixed and deciduous forests of the Russian Pacific combine northern elements from Siberia with southern elements from Manchuria, and have no analogues in North America or elsewhere. This is the only area of the FSU influenced by summer monsoons; 60% of all rain falls between July and September. The summers are warm (the average temperature of Vladivostok in July is +17?C), but winters are very cold (the mean January temperature is -15?C, colder than Moscow's). These forests have the greatest tree diversity in the FSU, with over 70 species. By comparison, the mixed forest in the Moscow region has at most 15 species. (Parts of New England, on the other hand, have over 70 species of trees, and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park has over 130!) Korean pine, two firs, two spruces, four lindens, and a few oak and maple species are the dominant trees in the north, along the Amur River. In the south near Vladivostok, walnuts, elms, and other southern species with Chinese affinities become more prominent. Actinidia is a common large vine, and Siberian ginseng and lemon-scented Schisandra are common in the understory. On Sakhalin and the Kurils, even bamboo can grow among the fir and spruce trees! The Amur tigers, of course, are the flagship animal species of the Far Eastern forests, numbering in the low 400s. Other interesting mammals include brown and Himalayan black bears, Far Eastern leopards, elk, wolverines, sables, lynxes, and giant shrews. Many rare bird species with limited distribution are found here (Blackiston's fish owls, Mandarin wood ducks, and blue and green magpies). There are 20 species of reptiles and amphibians here; although the state of Virginia (at a comparable location, but farther south) has 67 species of reptiles, these numbers are the highest for Russia. Turkmenistan deserts have over 40 species of reptiles. The azonal communities of the floodplains, lakeshores, and marine coasts occur everywhere near water, regardless of the natural zone they are in. The river floodplains and lake shores have tall meadows and emergent marshes composed of a few dozen widely distributed species (e.g., cattails, reeds, bullrushes, sedges, grasses, and other wetland plants). Likewise, marine coasts have a rather uniform set of species in the tidal zone (brown and green algae, barnacles, sea urchins, sea anemones, and a few flowering plants), all adapted to saline water and fluctuating tides. In the FSU, the most diverse marine life and the highest productivity of marine life are found along the Barents and White Sea coasts and in the Pacific. The Black Sea, in contrast, is a species-poor basin, because of the extensive anaerobic hydrogen sulfide zone in its depths and a high degree of local water pollution. The Baltic Sea has an intermediate degree of productivity and is the freshest of the major sea basins of Russia. |

|

| Sites web | |||